At the time of writing we are all still reeling from the devastating massacre of school children in Newtown, Connecticut. But this is not only because it was so unexpected and violent. How can we begin to understand (let alone move beyond) the cruel fact that most of those who were slain were children between the ages of 5 and 10? The wholesale slaughter of the innocent should rightly evoke anger, despair and even disgust at the dark power of humanity. As President Barak Obama said in his tearful address to the American people “Our hearts are broken.”

Reflecting a little more on this event and some of the reactions (appropriate or otherwise!) I wonder if perhaps what haunts us most about Newtown is the brutal, unavoidable reality of evil in the world and the devastating suffering it can produce on our very doorstep. It is easy to become desensitised to the bloodletting that erupts in global hot spots. The slaughter of the innocent is conveniently transformed into a tidy update on global affairs in an evening news broadcast. But Newtown is painfully familiar. This supposedly average middle class suburb with local institutions, challenges and comforts we would know all too well has been shattered by something unthinkable. Possibly what unhinges all of us a little is the realisation that this nightmare could be ours. And so could the devastation.

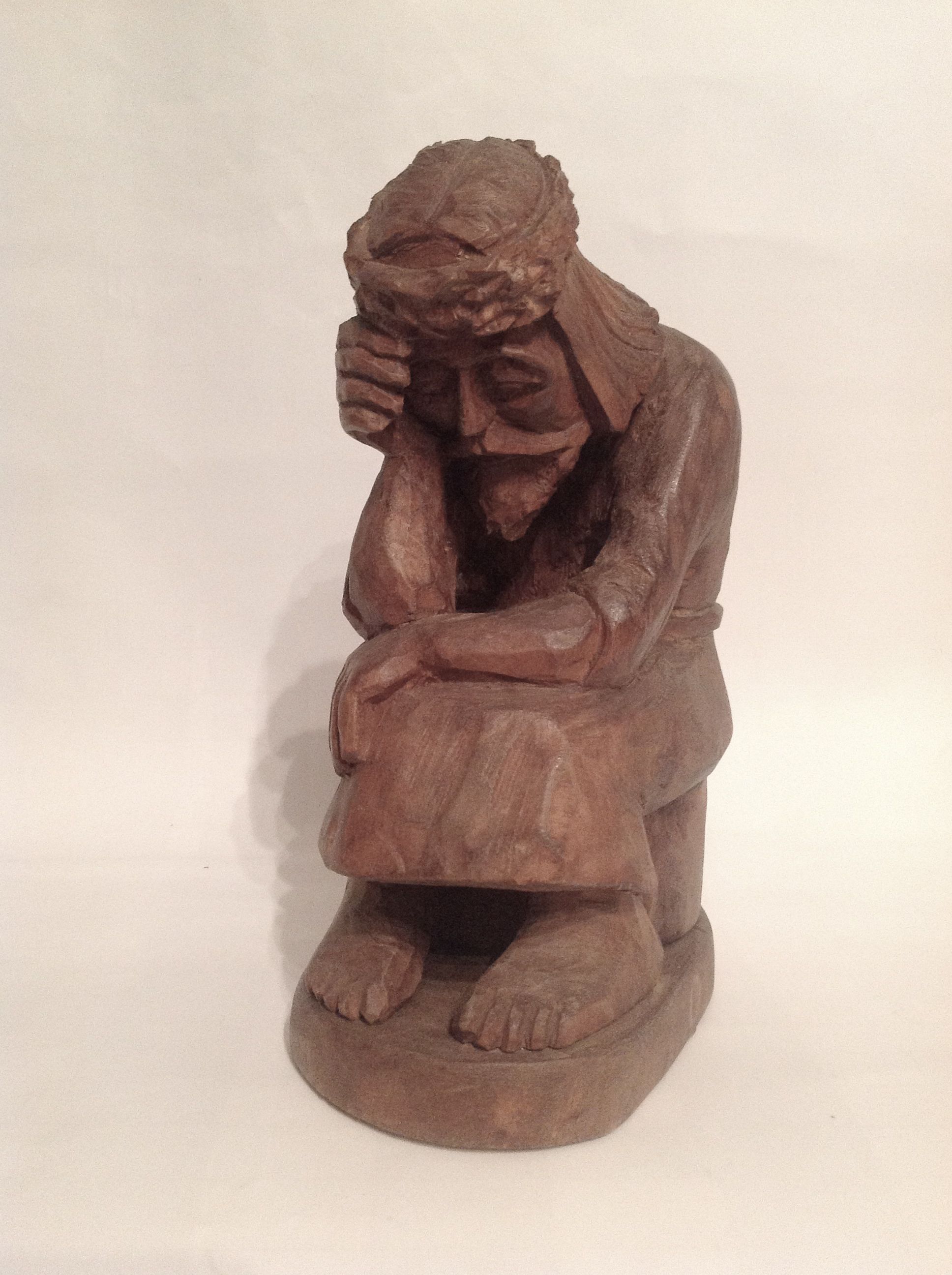

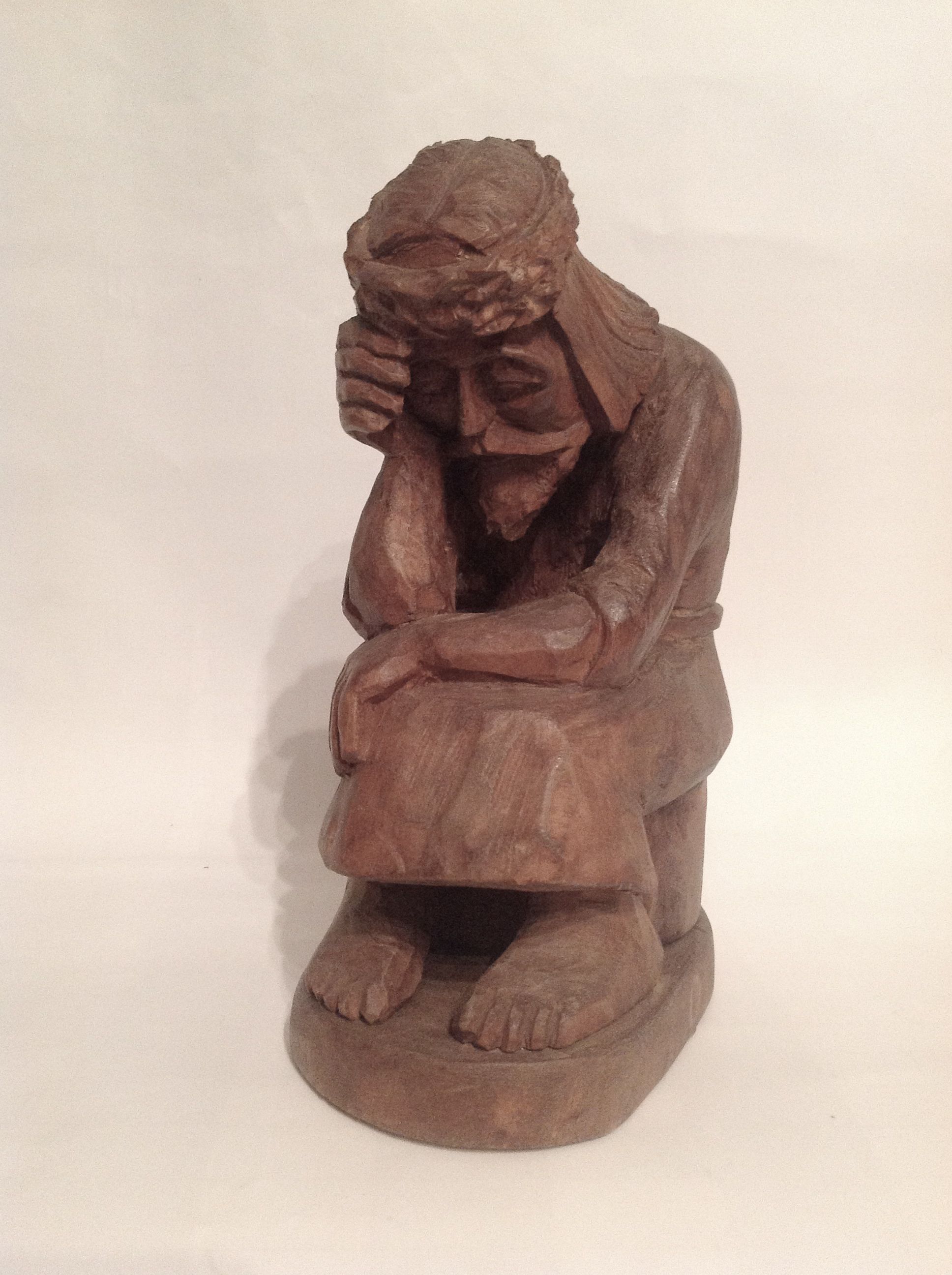

Just by chance I was handed something at the early morning service on the Sunday following the shooting. It is a piece of Polish folk art called “The Weeping Jesus” which belonged to a long time parishioner of the church. Almost immediately, it brought to mind John 11:35 “Jesus wept.” This is the shortest sentence in scripture and as a result is easily glanced over or even ignored completely. However, this stark and simple description of Jesus’ reaction to the death of his friend Lazarus is a profound symbol of the Christian faith. In fact, it is to my mind the real reason why we celebrate Christmas.

These two words convey the compelling consequences of the incarnation – God through Jesus is not just with us in the sense of being present, God is actually fully immersed in human experience in a way that is as intimate and immediate as our own experience. To put it more simply, God doesn’t just suffer with us, in Jesus (and in particular in Jesus on the cross) we believe that God became the full potential of all human suffering.

As Christians we should not be tempted to offer trite or well-worn phrases of comfort for the bereaved families and community of Newtown. We do not believe in a God that simply speaks soothing words in the face of human frailty and devastation. Instead we believe in a God who was “crucified, dead and buried”; a God who was utterly soaked in human suffering. We proclaim the power of a saviour who enters the world as a powerless baby, wept when he finds his friend dead and was terrified by the excruciating execution that awaited him.

Do we have the courage to believe that God was soaked in the cocktail of terror, anger and heartbreak of Newtown on 14 December 2012? Can we risk believing that Jesus wept? And as disconcerting as it may seem at first glance, is our faith in the strange circumstances surrounding a squalid and forgotten stable in Bethlehem the very reason to sing with conviction on Christmas day: “Joy to the world, the Lord is come”?

Justin Dodd

Justin Dodd  Thursday, March 21, 2013 at 05:39PM

Thursday, March 21, 2013 at 05:39PM